Cleaning up contaminants

In this Story, we’ll explore removing a contaminant from within a porous material by neutralising it in a chemical reaction. For example, the contaminant might be a hazardous liquid chemical that has seeped into a porous building material like concrete. We’ll keep safe while doing this by making use of VisualPDE simulations to explore what happens.

To decontaminate materials in practice, we often apply a cleaning chemical to the surface of the concrete, and wait while it diffuses down into the concrete and neutralises the hazardous contaminant. It’s crucial to react away all the contaminant. Here, we’ll say the decontamination is complete when there is no contaminant left anywhere in the material, which will correspond to the simulations going completely white.

How long does it take?

The time taken to complete a decontamination depends on many things, including:

- properties of the chemical, such as the chemical reaction rate,

- physical parameters, including how deep the spill is, how saturated the material is, and how quickly the cleaning chemical can diffuse through the porous material to reach the contaminant.

The simulation below lets us explore the effect of one of these factors: the chemical reaction rate, which we’ll call $k$. Clicking in the simulation adds a blob of cleansing chemical into the material. In reality, this is usually applied just to the upper surface (indicated by a thick black line), but here we can play around and add chemical to wherever we like. Try clicking to introduce cleanser, and watch as the green contaminant is cleaned up. At any time, you can reset the simulation by pressing

To explore the role that the reaction rate plays, try adjusting the slider found just above the simulation, and see what effect clicking has now. For larger rates, the reaction is faster, and this speeds up the overall decontamination of the concrete.

However, there’s a limit to how much we can speed it up by just varying this one parameter: for very large $k$, the speed of cleaning is controlled by the rate of transport in the material, not $k$, so we can’t continue to reduce the decontamination time by further increasing $k$.

You might also notice that for small $k$ the contaminant is (slowly) reacted away in a large region, whereas for large $k$ it only manages to clean small pockets of contaminant, leading to sharp boundaries separating the cleansed and contaminated regions.

How much cleanser do we need?

In practice, an easy way to speed up the cleaning process is to add more cleanser. The following pair of simulations lets us see this in action. In each, we’re applying cleanser to the top of the concrete, but the simulation on the right is at double strength. Restart the process to get another look by pressing

However, this approach is both wasteful and potentially dangerous: the cleaning chemical might be a strong acid or alkaline (like bleach) and so could damage the concrete if too much is left over after the decontamination.

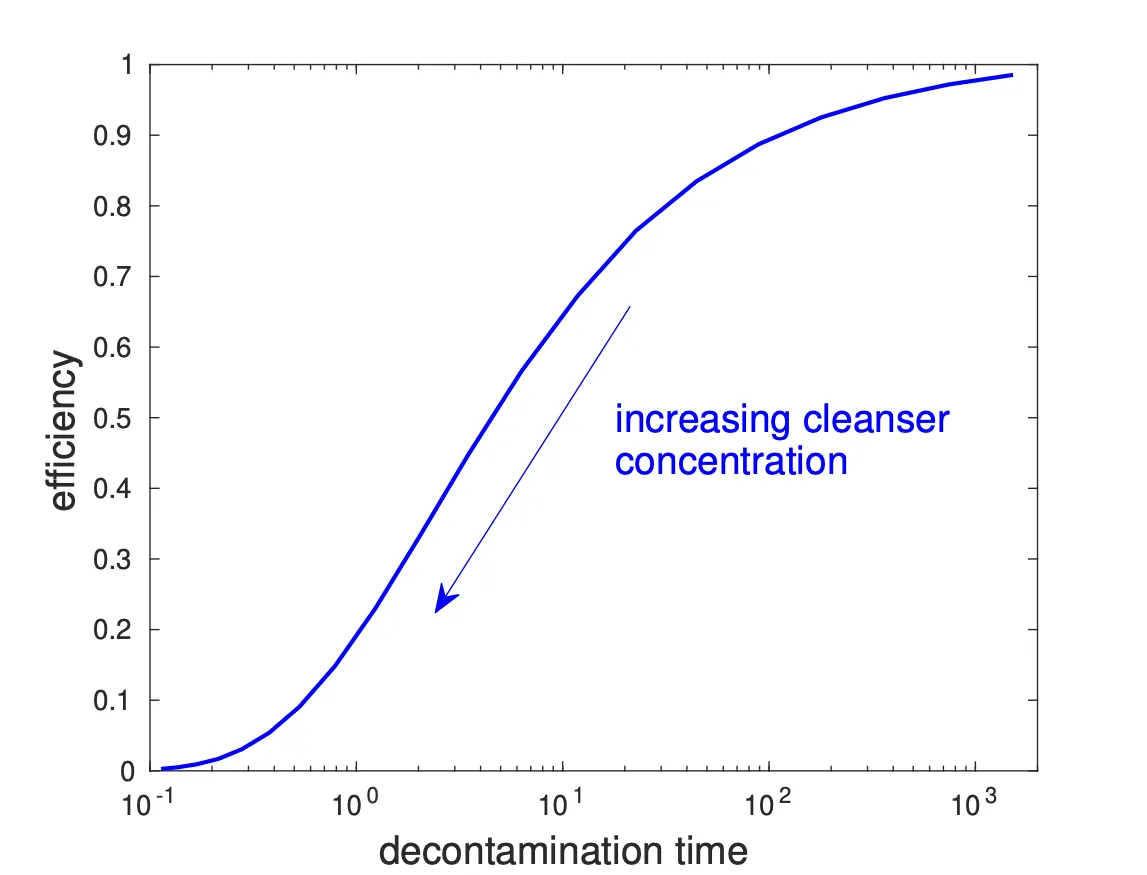

To measure this, we can define the efficiency of the decontamination process, which captures how much cleaning chemical is wasted: if the efficiency is 100% then all the cleaning chemical is used up in the decontamination, wasting nothing, but if the efficiency is low then lots of cleaning chemical is left in the concrete at the end of the decontamination.

Here’s a graph of efficiency vs decontamination time, where each point corresponds to a different amount of applied cleanser.

As we’ve already seen, we find that the decontamination is faster when we increase the cleaning solution strength, but it is less efficient. In practice, we would need to choose what strength of cleaning solution to apply (i.e. where on the curve we sit) to get a good trade-off between speed and efficiency.

This brings us to a final important question:

Is there a way to reduce waste?

Since the concentration of applied cleanser is the easiest thing to control, can we apply it in a clever way to keep the decontamination fast, but reduce the wasted cleaning chemical?

Let’s explore this with some simulations. We’ve set up two views into the same simulation: on the left we see the decontaminant, just like before, whilst on the right we see the cleanser (darker blue means more cleanser). The goal: make both simulations go pure white.

Use the slider below to adjust the strength of the applied cleanser throughout the decontamination process. A good idea is to start with a strong cleaning solution and gradually reduce the strength: this keeps the decontamination fast and the efficiency high. Can you find any better ways by exploring? Reset any time by pressing

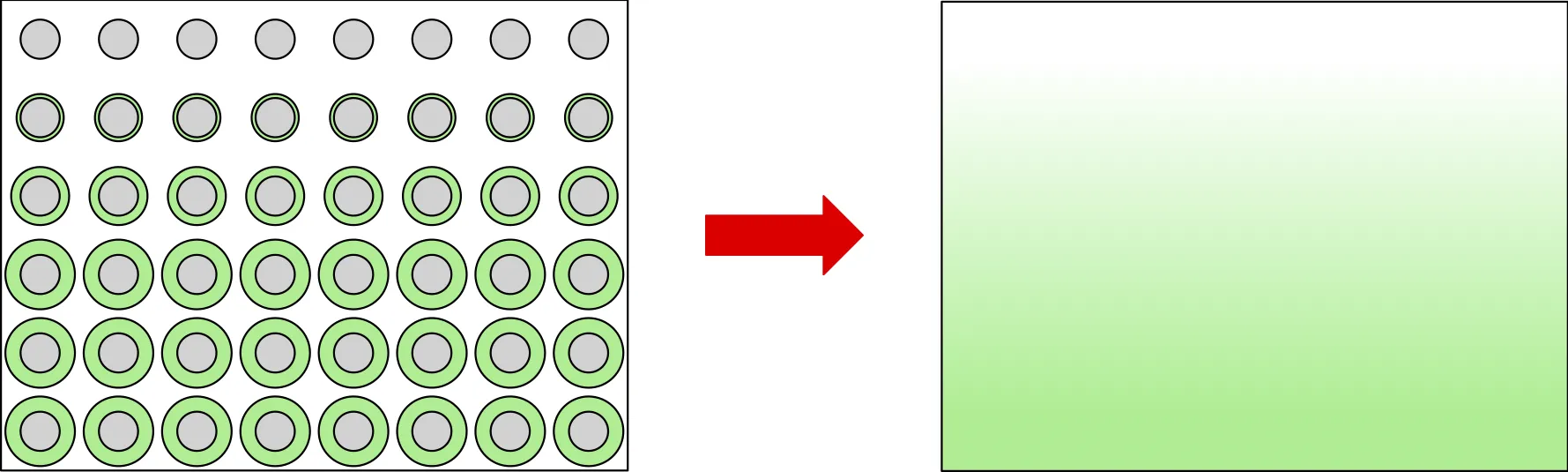

About the decontamination model

The mathematical model that we are using for these simulations is derived by considering the diffusion of the cleaning chemical and its reaction with the contaminant, within the pore space of the porous material. Rather than solve these equations in the very intricate, complicated pore-space domain, we’ve used a mathematical technique called homogenisation to average the equations. This makes them much easier and more computationally efficient to solve but keeps the important information from the underlying pore-space system. Specifically, the more contaminant there is, the harder it is to transport the cleaning chemical through the material, since the cleaning chemical has to navigate around the contaminant, in limited pore space. This manifests in the model as an effective diffusivity that depends on the local amount of contaminant.

You can find more details on the mathematics discussed in this Story in the following articles:

- Homogenisation problems in reactive decontamination (2019). EK Luckins, CJW Breward, IM Griffiths, Z Wilmott. European Journal of Applied Mathematics 31(5), 782-805.

- The effect of pore-scale contaminant distribution on the reactive decontamination of porous media (2023). EK Luckins, CJW Breward, IM Griffiths, CP Please. European Journal of Applied Mathematics 1-41.

- Optimising the Decontamination of Porous Building Materials (2023). H Turner. Masters thesis, University of Oxford.

Looking for more?

Not quite had enough of decontamination? To investigate other parameters in the model, check out this fully customisable simulation.

Enjoyed this Visual Story? We’d love to hear your feedback at hello@visualpde.com.

Looking for more VisualPDE? Try out our other Visual Stories or some mathematically flavoured content from the VisualPDE library.

This Story was written in collaboration with Dr Ellen Luckins.